There is no such thing as "talent" when it comes to drawing. That was the big revelation at the course I did a couple of weekend's ago based around the Dr. Betty Edwards school of learning to draw. Betty (no relation) advocates that anyone can learn to draw. It's not about your hands. It's about your eyes, how you see. And, Betty claims, anyone can train their eyes to be "artist's eyes". I liked the sound of that, so was interested to find out what I would produce by the end of the weekend using Betty Edwards' classic exercises.

The basic theory goes something like this: there are two sides to your brain. A right side and a left side. The left side is responsible for logic, knowledge, facts, language. The right side deals with intuition, feelings, emotion, instinct and importantly how we view things. In most people, the left side dominates. This can be a problem when it comes to drawing, because, the left brain will always tell us how something "should" look, according to the knowledge we have amassed. However, if we allow our right brain to take over, and trust in what we see in front of us, then our visual mode can kick in and we can draw exactly what we see, not what we think we should be seeing.

Here are some of the exercises we did to get that right side of the brain (and therefore the visual mode) working:

1. Upside-down drawing

For this exercise, we replicated a line drawing, only the drawing was upside-down. What this meant it that (for the whole part), your left brain finds it more difficult to put labels (like "head, eyes, hands etc.) on the parts of the image you are copying , so it drops out, allowing your right, visual, side of the brain to focus on drawing lines. Just lines. Not hands, or legs or anything. Just lines.

I was really amazed that I managed to (fairly accurately) reproduce the lines of this portrait of Stravinsky by Picasso. I never would have been able to draw those fingers and thumbs like that if I had thought of them as fingers and thumbs rather than as just lines.

2. Blind Contour drawing

With this exercise, you don't look at the paper at all. You just draw while the whole time looking at your subject matter. Again, this engages the visual mode of the right brain.

Your drawing will look complete rubbish, since you don't know exactly where you are on the page at any one time, but that's not the point of this exercise. The point is to use it as a "warm-up", to get you familiar with the subject. So that you get to know exactly what it really looks like (not what the left brain tells you it should look like).

3. Getting perspective - using a glass frame

Conveying a sense of depth is perhaps one of the trickiest things of all about drawing. How do you render something three dimensional on a two dimensional piece of paper?

Betty Edwards devised a method of using a glass or plastic "frame", through which you see your object and, closing one eye and keeping your head in the same place (so that the view doesn't alter), drawing the outline of the object directly onto the glass frame. Like this example with the outline of my left hand:

But she didn't invent this. Even the old masters such as Duerer used similar methods to understand perspective:

Once you've got the outline, it's easier to transpose this to paper, and then, using your actual object again as reference) fill in the remainder of the details.

Here's a banana I drew using the glass frame method, and then finishing off with details and shading by just looking at the banana (ie not through the glass frame):

4. Drawing the negative space

In this exercise, instead of looking at your subject and drawing its outline, you look at the negative space - the gaps between parts of the subject and draw those "holes" instead. To start with we did this with a fashion photograph from a magazine.

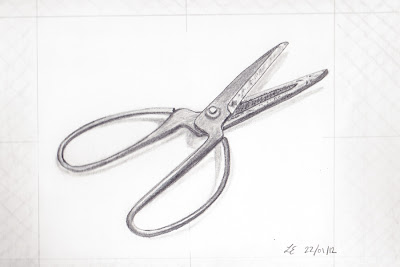

Then we combined this method with the method used in 3., above, to draw a real object in front of us, in this case, a pair of Chinese style scissors. To do this, we chose one "negative space" element to draw through the glass frame, then drew the same shape on paper and then continued working on paper, only using the frame as and when necessary to get an idea of the other shapes. Here's my final drawing of the scissors, using this technique.

5. Rendering light and shadow

Finally we considered different methods of creating light and shadow, stippling, applying different pressure to the pencil, using pencils of different softness, hatching and cross hatching. The picture below shows how you can give the impression of a three dimensional object using different degrees of cross-hatching.

I was really amazed with the drawings I produced using the methods advocated by Dr. Betty Edwards, and the techniques have certainly made me more aware of how my brain works and how this affects the process of drawing. Above all, I've learnt to trust in what I see (not what I think should be there), to give myself time (the left brain will always be impatient) and to PRACTICE, PRACTICE, PRACTICE!

Resources:

Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain, Betty Edwards

Munich Volkhochschule (Kurs "Zeichnen, aber anders")

.JPG)